G.S. McLennan

George Stewart McLennan was born in Edinburgh, Scotland on the 9th February 1883 and is still known simply as "GS". By the time of his death in 1929, he had progressed from being a child prodigy to one of the greatest pipers of his generation with a legacy of remarkable pipe music compositions which remain staples to a broad range of musicians to this day. For many in the world of piping - and the broader musical world - he is known for his fine compositions but little is really known of the man himself.

His image is readily identifiable but few have seen photographs of him out of the familiar military uniform or Highland Dress. Probably there is no-one now alive who will have heard him play, yet his playing is still spoken of in reverential tones.

Early Years

As is always the case, his formative years helped mould the adult he was to become. It must be remembered that he was brought up in Victorian Edinburgh, a very different world from that we inhabit today. He was born in St Leonards Street, Edinburgh to Lt John McLennan of the City Police and his wife Elizabeth Stewart. Both sides of the family had a strong traditional of piping - particularly the paternal side where this stretched back for many generations in Rossshire and Inverness.

The fact that GS was unable to walk for the first few of years of life simply adds to his legend. The cause is not documented but 'polio' is frequently referred to - perhaps just used as a generic term for difficulties with mobility at that time. However by the age of four, he was both fully active and already demonstrating an innate musical ability as his father taught him the pipes.

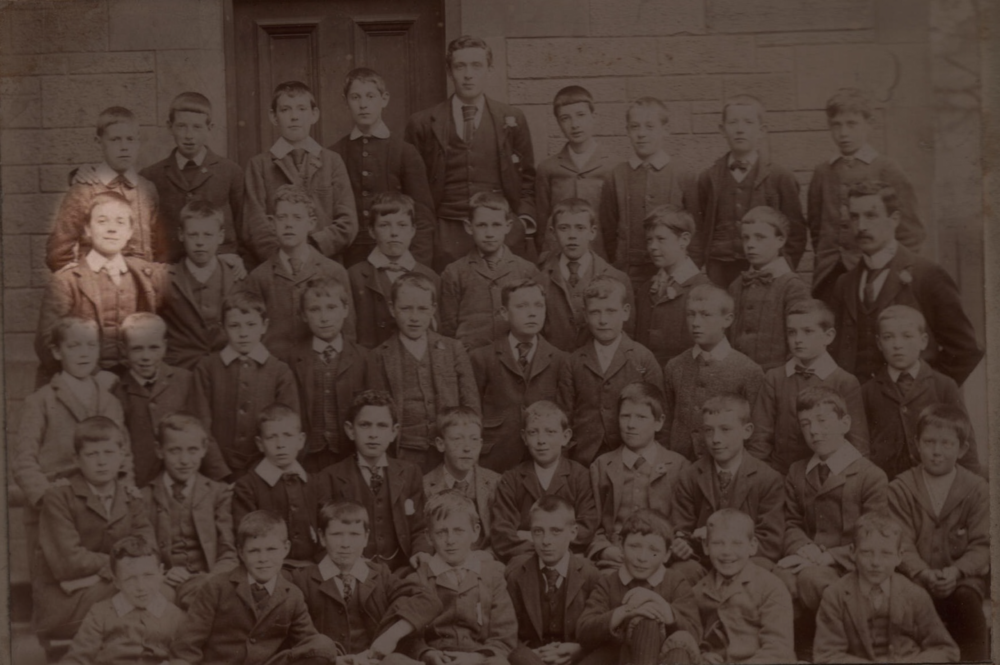

The city and the Royal Parks were the playground for GS and his contemporaries as children. The family lived close to the parkland around Arthur's Seat and Salisbury crags - not perhaps to be considered the safest of play environments from a 21st Century perspective. School photographs reveal a child exuding self assurance and confidence - and perhaps a hint of mischievousness. As a teenager, he would visit the port of Leith where he attended the Naval Training Ship "Redwing" and he soon harboured hopes of a career in the navy.

Unlike his friends, GS lived a parallel life of what would today be considered "hothousing". His father, Lt John McLennan, came from a long line of McLennan pipers and possessed a phenomenal knowledge of technique and history. GS was an able and willing pupil from a very early age, perhaps having been inspired by the presence of his cousin William MacLennan. Lt John's brother George died young and his son William came to live with this other branch of the family. A remarkably gifted champion piper and dancer, he too was to die young, but part of the great legacy he left was the impression he made on GS. Every teacher provided a key to young George's musical development - what William gave to GS was the understanding that established boundaries were not limits, a revelation which was to manifest itself in many of his compositions.

Further piping teaching came from the renowned John MacDougall Gillies and Pipe Major John ("Jack") Stewart from Dundee, his maternal uncle. The former will have reinforced the technique, discipline and performance skills but the much loved uncle Jack had an additional reputation for flair and fun. All these four named men must be fully credited as being (literally) instrumental in the development of GS as a musician.

Lt John was obviously keen to push his young protege, entering him to dance and piping competitions from an early age. Having appeared by Royal Command before Queen Victoria at Balmoral aged just 11, his moment of fame was fully exploited. His youthful public appearances always refer to this event and no more so than when touring the country with "Lumsden's Popular Concert Company" at the age of 14. ("The Celebrated Boy Dancer and Piper who appeared by special command before Her Most Gracious Majesty"). It is apparent that GS took none of this for granted and worked hard and honed his skills throughout these years.

The death of his mother when he was still of primary school age will have had a significant impact as will the arrival of a stepmother with two young children of her own. It was rumoured that the subsequent increase in the number of his siblings partly led to his being sent off to a life in the Army. One thing is for sure, GS later told his sons that one thing he did learn from his father was how not to be a parent. It would seem that Lt John was a rather stereotypical Victorian father driven to push his talented son forward. That relationship however did not mean there was no mutual love or respect between the two. The McLennan family are in possession of GS's side of a prolific correspondence between the two - albeit largely on the subject of piping - and GS frequently passed manuscripts to his father for parental criticism (in the most constructive sense).

The Gordon Highlanders

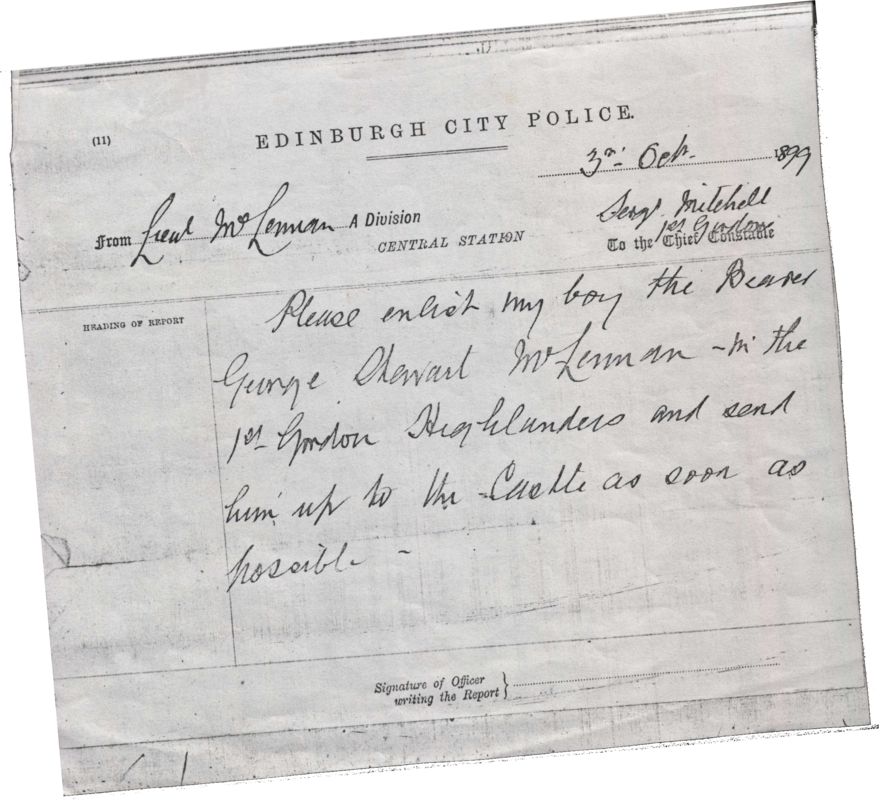

One of the best known anecdotes regarding the life of GS McLennan is of his recruitment to the Gordon Highlanders. Lt John handed GS a letter which he was required to deliver to Sgt Mitchell of the Gordons at Edinburgh Castle. The young George duly complied. Sgt Mitchell retained the letter and on his retirement returned it to GS - it remains in the family - the Sergeant apparently quite appalled by the seemingly cold act it initiated.

Dated the 3rd October 1899 it read :

"Please enlist my boy the bearer George Stewart McLennan in the 1st Gordon Highlanders and send him up to the Castle as soon as possible"

Within the month GS was serving in the Army. The Anchor & Heart tattoo on his forearm a permanent reminder of his thwarted hopes of going to sea.

But life in the Army had not started smoothly for the young and diminutive GS. Aged 16 and only 5 foot 2 inches at the time he joined up, he was an easy target for bullying. His reaction was to get hold of a "Teach yourself ju-jitsu" book and learn this art of self defence. After the first couple of times the bullies had to pick themselves off the floor they got the message that this was not a man to mess with. Here was a man who would earn respect of his comrades as he had done in dancing and musical circles.

GS did not become the then youngest Pipe Major in British Army history by chance or luck. His ability on the pipes was a given, but it was his self-assuredness, natural authority and skills with people that made him an obvious contender. In fact this was just a very natural progression from what had gone before.

Three of his postings with the Gordons would have significant consequences for his life. His two postings to County Cork - particularly the first in the early years of the 20th Century - would have a big influence on him musically. He soon got to know local musicians and got to know more about Irish music and piping and this continued to be a great interest throughout his life. And of course he had a great affinity for the Irish people, despite his being there with the largely unwelcome British Army. It was here that he wrote and named his first completed major composition "Kilworth Hills" for the area north of Cork that appealed so much to him.

His posting to Colchester affected another area of his life, for it was there that he met and married Nona Lucking, the daughter of a local taxi driver. Soon afterwards GS was posted to the Gordon's Depot in Aberdeen (the home city of the Gordon Highlanders and today the site of the excellent Regimental Museum) and she was swept into a different world with what seemed to be a different language.

The third of the significant posting was to France in 1918. GS had 'missed' most of the War, being retained at the Gordon's depot in Aberdeen but of course you didn't need to experience much of the Great War for it to have a significant impact. Although he left copious notes on many subjects, his diary for that year recorded little of detail. The entries for May casually understate events.

Friday 17th May : Hospital T7. Addmitted (sic) Canadian 4th CCS (Casualty Clearing Station)

Wednesday 22nd May : 8oz fluid from left breast

Saturday 8th June : Left 4th Canadian CCS for Battalion... very weak... billeted in loft for the night

He had actually collapsed at the front as he refused to 'desert' his men despite knowing how ill he was. The fluid had been drained without anaesthetic which left him permanently scarred and following partial recovery he was left to make his own way back to the Battalion. However, true to form this last entry of 8th June has a more upbeat postscript : "Met P/M Gillies (late Scots Guards) and the 2nd Seaforths Pipe Band".

As a P/M he was well respected by the band members. He would encourage and develop younger members wherever possible and several bandsmen went on to become Pipe Majors in their own right and even (as in the case of James Robertson) as excellent composers. His continuing friendship with 'Robbie' included a rivalry about which of the two was losing their hair fastest and most severely. GS was to claim victory in this battle by composing a tune specially for P/M Robertson entitled "Lament For Robbie's Last Two Hairs Destroyed by Worry" in 1923.

On the 26th June 1922, GS McLennan was discharged from the Army after 22 Years and 233 Days. His Discharge Certificate reveals that he had grown to a mighty 5 foot 7 inches. His Character Certificate reads :

"In every respect exemplary. An excellent Pipe Major - most courteous & obliging. Has not had any charge against him in 22 and a half years service."

In Competition

GS had been competing in dancing and piping competitions from a very early age. Aged ten he had won the Amateur National Championship for marches, strathspeys and reels. In 1894 and '95 he won the Scottish Amateur Championship for piping and just one year later he triumphed in the London Highland Amateur Championships for piobaireachd, marches, strathspeys and reels. Furthermore, GS had also won the Scottish and English Amateur Highland Dancing Championships in 1895. In those days, it was a natural pairing for pipers to be able dancers too - Angus MacPherson is another example - but to achieve so highly at such a young age is rare. Undoubtedly GS possessed a remarkable natural sense of rhythm and timing.

Thus by the time George found himself in uniform, he was already a weel kent face (and sound) on the competition circuit and was achieving considerable success. It has been said that the new wave of talented young pipers began to drive some of the older competitors into retirement and this was indeed a golden age for piping talent. It is immediately apparent that this new group of pipers became a tight knit community in their own right with genuine friendships developing.

Army postings often meant he was unable to attend competitions, most of which were held in Scotland while GS found himself isolated in Cork, Aldershot or Colchester. Transport and accessibility were not as quick and simple as they are today and some officers were less than sympathetic to allowing extended leave of absence. One such CO actually asked GS if he would dedicate a tune to him on his retiral. Unsurprisingly this was given a negative response.

His achievements included winning the Oban Gold Medal in 1904, that of the Northern Meeting in 1905, followed by Clasps at Inverness in 1909, 1920 and 1921. Fifteen appearances at the Aboyne Games between 1904 and 1927 gave a return of 15 1st places for Marches. In total he is supposed to have won some 2000 competitive piping awards in his curtailed career.

A fine example of camaraderie comes from 1927 following an incident at Inverness in which Willie Ross was disqualified from competition due to his failure to appear in time for the grand march. GS duly refused to compete unless Ross was reinstated. Willie Ross later wrote to GS saying...

"It touched me very much when I heard of the attitude you took up in my favour... you were always my best friend and in fact longest acquaintance as a competitor.". In this letter he concurs with GS that "...the people who did the dirty on me at Inverness mean to see us off".

In fact GS was relegated in the judging as a consequence of his protest and Ross admitted that "even my mother knew who should have got the MS & Reel open". As with their arrival on the scene 25 years previously, this heralded their recognition that there was again a changing of the guard at competition.

Many of GS's medals are today held in the Scottish National Museums collection in Edinburgh Castle, and are generally on display to the public. A few remain in the family and many have disappeared - GS's brother, John, would allegedly give them to interested customers in his Edinburgh pub and some things vanished from the family house which was let out during the Second World War.

Out of the Army

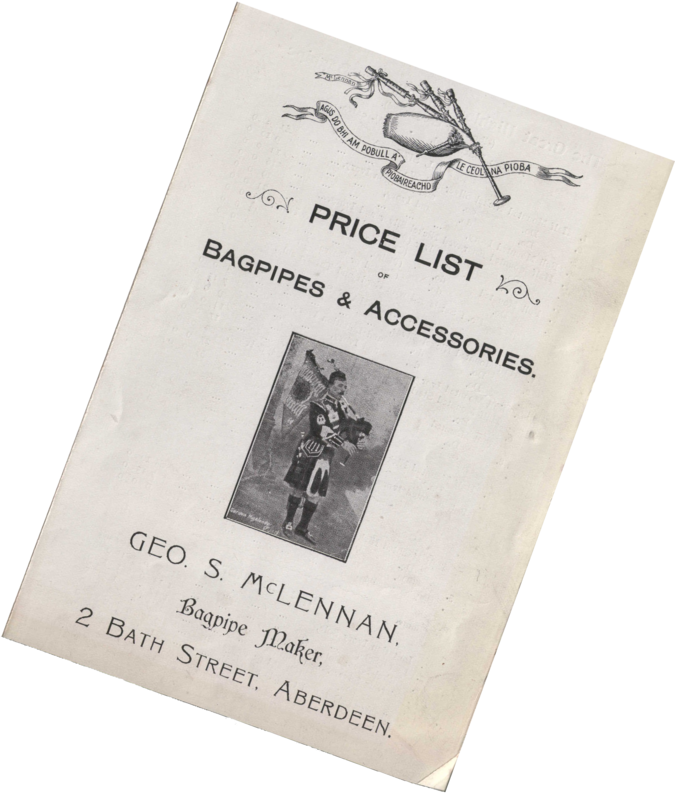

GS had prepared well for leaving military service. Before the War he had manufactured his first set of pipes and had also started to make pipe reeds. Life for soldiers in the War swung from the stresses, fears and traumas of action to long sustained periods of boredom. George McLennan filled these times productively. When not working with the pipe band he would practise playing, note down and develop pieces of composition and make reeds. The reed he sold to pipers in France and sent others back home for sale locally, thus building up a nest egg to top up his small army pension.

In 1922, immediately on leaving the Army, he bought a small shop in Bath Street, Aberdeen and continued to make and sell pipes, chanters and reeds together with bought in goods. And of course he had a further small income from competition prize money. The authors of the Gordon Highlanders Pipe Music Collection included a biography of GSM in Volume II much of which had been gleaned from GSM's surviving son, George. However in the text they relate an anecdote about a customer visiting GS's shop which includes the alleged quote "Do you know who you are speaking to? I am George S. McLennan!". In George McLennan's personal copy of this book that paragraph is heavily scored through and the comment added above "GS would NEVER have said anything like that!!!". It does indeed seem totally out of character and the evidence supports 'young George's' view of the matter.

By this time he and Nona had two children. George had been born in 1914 and John Hector two years later. On being posted to the Gordon's Depot in Aberdeen in 1913, GS had moved his wife to a private house, as he did not believe Edwardian Army married quarters to be a pleasant environment for his wife who was also new to army life and the city. They soon settled in a cottage situated behind the tenements of Powis Place in the centre of the city and not far from the Castlehill Barracks. GS taught both his children to play the pipes with John the more confident and with the prospects of a great future in playing and competition. GS was able to spend time as a family man and make use of his own childhood experiences in his role as a father. Unlike Lt John GS believed as he told his sons, that a father should be "more like a big brother" - perhaps reflecting on his relationship with his older cousin William. Certainly Lt John McLennan would never have been photographed, as GS and Nona were, skipping during a visit to a Scout Camp. GS was a 20th century man with a serious commitment to his work and music but a genuine light-hearted love of life and family.

Sometime after returning from France the family held a meal with Lt John McLennan and his wife. There was no room at the table for young George - then about 4 years of age - so he had to sit and eat at the hearth. Jealousy set in as his wee brother shared a table and the attention of the adults. By the time a milk pudding was served he had had enough. He stood up, walked to the table and decanted the bowl over his younger brother's head. There was silence in the room as Johnnie sat patiently with the semolina dribbling down his face. Mrs McLennan (senior) broke the silence by demanding that GS "Take that boy out and punish him!". Respecting his stepmother's wishes, GS grabbed young George and dragged him to another room and those sitting round the table were treated to the sound of resounding slaps and cries. The two returned then to the room, GS looking flushed and angry and young George looking remorseful and tearful. The stepmother looked well satisfied, but might not have been if she'd known of what went on out of her sight. GS, genuine tears running down his own face, told young George that this had been "the funniest thing he'd ever seen" and the two had acted out the whole "punishment". He was indeed a father unlike that which he had experienced.

The only recordings of GS McLennan playing pipes were made as a young boy to wax cylinders in the 1890s. When given the opportunity to make professional recordings to a 'modern' record as a young man, he was denied the opportunity by his Regiment. Once out of the Army, he protested that he was past his best and did not want to be remembered through a lesser performance.

GS continued attending Games and Piping Competitions in retirement with generally continued success. However, his health was never fully restored after that illness in France (possibly pleurisy?) and it certainly would not have been helped by his continued smoking habit as was so common at the time. He suffered several periods of severe illness during the 1920s and the MacPhersons at Inveran would take him in to their Highland hotel to help him recuperate where GS rewarded their hospitality by gifting them two of the finest pipe tunes ever created.

( Not the ) End of the Story

There is considerable myth built up surrounding the circumstances of GS McLennan's death, generally the result of press reporting of the day. The tabloid press, just like today, knew how to spin a story to add shock, luridness, or in this case pathos. One contemporary headline read "Bagpipes of Death!" another "Piper plays his own deathbed lament".

Each evening, GS had continued to give tuition to his sons (then aged 14 and 13), right up until the night he died. On the evening of 31st May 1929 they were working on his own composition "Dancing Feet". Demonstrating the correct manner of playing one 'G' grace note, young John blew the practise chanter as GS showed the fingering. At this point his fingers slipped from the chanter and he lapsed into a coma from which he was not to wake. His wife, Nona, and the two boys were with him when he died. The cause of death was recorded as "Carcinoma of the Lung. Secondary Carcinoma of Larynx. Cardiac Failure."

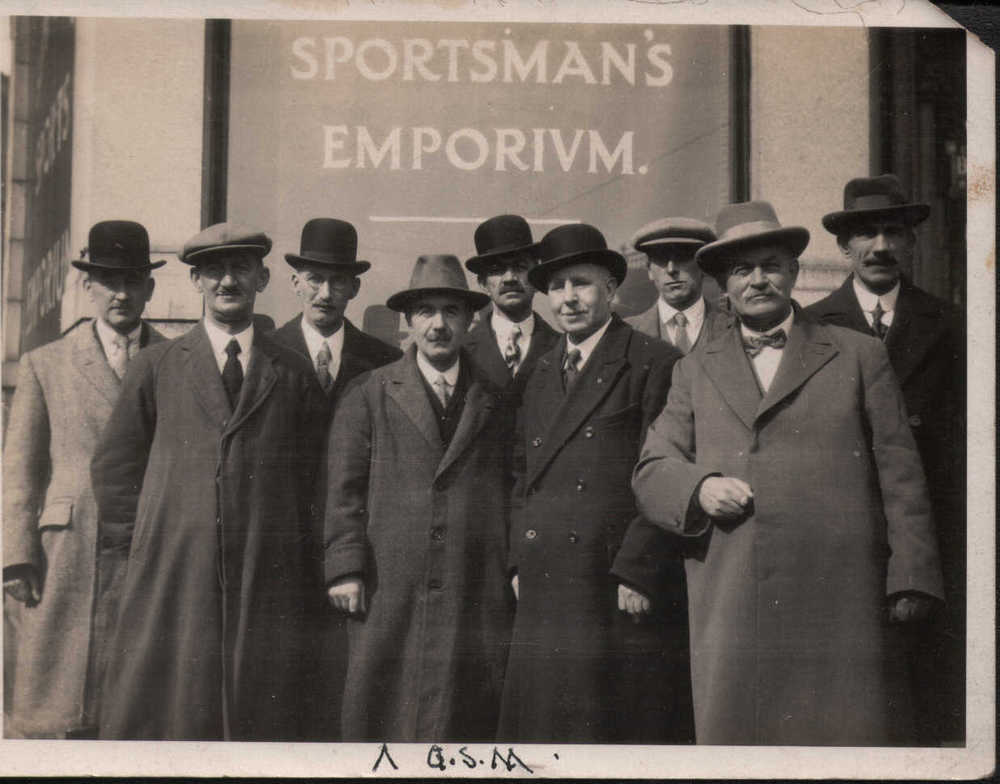

His funeral took place on the 4th June 1929 with an estimated 20,000 people lining the streets of Aberdeen between the family home and the railway station. His coffin was borne on a gun carriage preceded by three pipe bands - that from the Depot of the Gordon Highlanders, the British Legion and a third comprising fellow competitors from Highland Games. The cortège was headed by his young sons who had to endure this emotional and very public walk through the city. Nona, in common with most wives at that time, was excluded from the public aspects of the funeral. Others in the party included Pipe Majors Findlater VC, James Robertson, George Cruichshank and Bob Nicol together with friends and representatives of many organisations.

The coffin was taken by train to Edinburgh were he was interred in Echo Bank Cemetery (now Newington Cemetery) with his father, Lt John McLennan. Pipe Major Robert Reid of Glasgow played "Lament for the Children", GS's favourite piobaireachd.

Legacy

At the time of writing, George Stewart McLennan is approaching his 135th birthday. But his works remain as popular as ever - if not more so. Despite there being no-one to remember hearing his playing, that too is spoken of with utter respect - in fact a recent poll organised by pipes|drums.com placed him as the 3rd greatest piper of all time. He would surely have been proud to still be spoken of among those other great 'rivals' in that poll one century on.

His tunes have crossed genres to become staples of the accordionists and fiddlers of Highland Dance Music and increasingly his compositions appear in the live and recorded works of contemporary bands worldwide. With his background and love of music there is no doubt that he would have appreciated (although perhaps not enjoyed!) all these new versions provided they were well played. With limited record sales in the 1920s and with his "Highland Bagpipe Music" book published just a month before his death, he received little in royalties and sales - his compositions were never to prove lucrative to him.

In 1950 - 30 years after his death - a previously unpublished march by GSM won a competition organised by the Braemar Highland Society and became his first posthumous new work. The balance of his compositions which had remained in his manuscript books after his death finally saw the light of day in the 1980s in the Gordon Highlanders Pipe Music Collection, Volumes I and II. There remain many scraps of tunes which were never fully developed as do several drafts for piobaireachd.

Since then he has been remembered in several ways, each highlighted in the "Legacy" pages of this website's museum. A Memorial Piping Competition held in the USA; an exhibition of his life and work; a commissioned portrait presented to the Gordon Highlanders Museum; a plaque erected outside his shop in Aberdeen.

But above all his finest memorial is in the music that so many people on so many different instruments in so many musical styles perform professionally or for pure pleasure throughout the world every single day.